Not a year has passed since the world was shocked at the tragic news of the death of one of its most prominent architects, Zaha Hadid. The Iraqi-born British architect is arguably the highest accomplished female in the profession. With more than 950 buildings in 44 countries and an extended list of prestigious awards, she has firmly proved her statement that “architecture is no longer a man’s world.” Zaha’s long and winding road to success starts with “a fabulous childhood” and passes by 5 milestones of ups and downs which have shaped her future as we know it.

“Architecture is no longer a man’s world. This idea that women can’t think three dimensionally is ridiculous.”

Zaha Hadid, Veuve Cliequeote

Courtesy of The Hyatt Foundation.

Zaha Hadid was born in the early 50s and lived her childhood during the brief golden years of modern-time Iraq. The ruling government back then, decided to put the increased national share of Petroleum money to use by bringing on pioneers of modern architecture, like Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, and Walter Gropius, to modernize the city of Baghdad, issuing a hopeful atmosphere. There were, also, Zaha’s liberal parents who have encouraged her curiosity and brought her up to be independent. All of which contributed to her strong and confident personality, showing its first sign by the age of 11 when she decided that she wanted to be an architect. Her father was a business owner as well as an active political figure, and her mother was an artist.

Courtesy of The Irving Penn Foundation.

Milestone #1: Making the Decision – Architecture it is

Zaha Hadid could have been the first Iraqi astronaut, or that is what her brother used to say. However, her passion for architecture never faltered, and her mother supported it by letting her do the interior design for the guest room and her own bedroom.

Most of her schooling was done in the boarding schools in England and Switzerland. So, as soon as she graduated from the Department of Mathematics at the American University in Beirut, she headed to London and joined the Association of Architecture (AA).

Zaha Hadid, the child!

“I had a fabulous childhood…” Zaha described her life in Iraq when it was in 1950’s in its peak.

Milestone #2: Making a difference – Graduation Project

After three years of weariness from studying the stable architectural movements of the time, Zaha decided to, finally, make a difference in her fourth year. She decided to break the prevalent stability by introducing a style which she described as follows: “It was very anti-design. It was almost a movement of anti-architecture.” It was influenced by Suprematism, a Russian art movement, founded by Kazimir Malevich, which employs basic geometric shapes in a limited range of colors. That influence was clear in her graduation project, in 1977, when she fragmented and abstracted one of Malevich’s works then reshaped it into a new form. Zaha’s remarkable talent, commended by her teachers, Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, was immediately put to use after her graduation. She was appointed as an assistant lecturer in the AA and made a partner in OMA, with her teachers, before launching her own studio in 1979. Hadid was the Kenzo Tange Professorship and the Sullivan Chair at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s School of Architecture. Her first project was Vitra Fire Station. She has also taught in Harvard Graduate School of Design and served as a guest lecturer at the Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg (HFBK Hamburg).

Photo via A/N Blog.

Milestone #3: Working Hard – Reaching the Peak

Zaha’s life after graduation was a series of hard work, teaching by day and working by night. The hard work seemed to pay off in 1982 when she won the international competition for designing a leisure club in Hong Kong. Zaha’s distinct Suprematist style of presentation grabbed the attention of the jurors and gained her an unexpected victory. This milestone was one big up in Zaha’s career; it changed everything, just like Elia Zenghelis has said: “The Peak was the peak and still remains a peak.” It placed her on the map and made her studio the destination for many aspiring architecture students, including Patrick Schumacher, her future Studio partner. For all that, Zaha’s winning proposal was never executed; that and many others that followed which were criticized for being ambiguous. She got labeled as a “Paper Architect.”

Painting – Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Milestone #4: Frustrating Rejection – A Career in Jeopardy

Finally, after many attempts at making it into the 3-dimansional realm, Zaha won the competition to design Vitra Fire Station in 1990. The design, titled “Movement Frozen,” featured a pure concrete block with angular edges that seem to be stretched to a focal point. The unique form gave a new meaning to the use of concrete. According to the architectural photographer Hélène Binet: “She has created an incredible signature. Concrete became something else, I think, after her.”

That was the light before the dark that came with the Cardiff Bay Opera House project. Zaha’s win for the first prize in the competition, in 1994, was a cause of controversy and harsh criticism from those who believed her design to be inapplicable. The negative attitude towards the proposal was incomprehensible to Zaha who thought: “The plaza sections are not the same as a normal building. It is not a square building or a rectangle. That project was easily… Could be easily done.” All the ruckus has deeply depressed her to the extent that she, actually, decided to quit architecture.

Painting – Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Milestone #5: Unprecedented Glory – Hard Work Pays off

Luckily for Zaha and the world, Patrick Schumacher was a great motivator and supporter. He helped bring her back to her feet and snatch Zaha Hadid Architects from the recession caused by the Cardiff “Curse,” to start their golden age with the new millennium.

The 2000s have witnessed many of Zaha Hadid’s designs coming to life finally, thanks to the developed technologies which have rendered them possible. Her designs became international landmarks, widely celebrated and admired by both, the architectural community and the public. In 2004, she was awarded the Pritzker Prize, the field’s most prestigious award, to be the first female ever to achieve such an honor. Then in 2012, she became Dame Zaha Hadid, after getting appointed as Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DME) which is the considered the “Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.” Her last triumph, before she leaves this world at the age of 65 after a heart attack, was the recognition by the RIBA who granted her the 2016 Royal Gold Medal to be again the first female honored with a highly-esteemed architectural award.

Zaha Hadid has carved her name deep in history with her outstanding architecture and extraordinary accomplishments. People may not know all the hardships she faced to get her name where it stands now, but they, certainly, know that she is a figure worthy of utmost respect and a sure proof of what women are capable of. Her designs are skeptical attitude of post-modernization. They depict the chaos in the modern life. She lately worked on as a professor at University of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria.

Painting – Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Vitra Fire Station – Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Rendering of Vitra Fire Station – Courtesy of Zaha Hadid

Painting – Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects.

Her Legacy

From 2010, she was a guest Professor at the University Of Applied Arts Vienna in Austria. Hadid has accepted high profile interior work for Mind Zone in London. She has also created fluid furniture installations within the surroundings of Georgian Home House private members club. She designed Moon System for B&B Italia in 2007 and designed Liquid Glacial in 2013. Hadid owns a design firm, Zaha Hadid Architects that is headquartered in London.

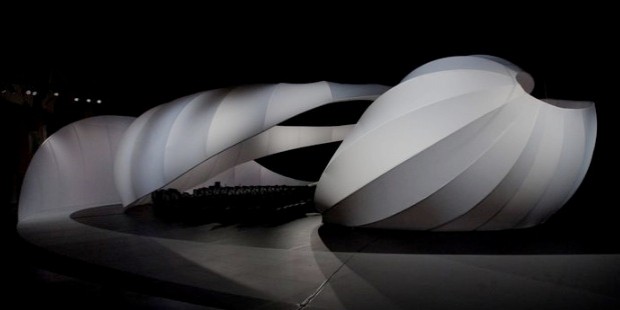

Zaha’s work include Vitra Fire Station, Bridge Pavilion, Chanel Mobile Art Pavilion, Riverside Museum, London Aquatics Centre, Evelyn Grace Academy, Guangzhou Opera House, Galaxy SOHO, Phaeno Science Center, Sheikh Zayed Bridge, Jockey Club Innovation Tower and Salerno Maritime Terminal.

The latest to add to her completed designs include Investcorp Building, Citylife office tower and Dongdaemun Design Plaza in 2014. Currently Zaha is working on 11 projects that also include Esfera City Center in Monterrey, Iraqi Parliament Building in Baghdad, 520 West 28th Street in the United States and Dominion Tower in Russia.

Heights and Notable Works

Hadid was an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and also an honorary fellow of the American Institute of Architects. Hadid was given the Honor of Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 2012. She is the highest paid architect in the world.

Projects that were Built

- IBA housing in Berlin, Stresemannstraße. 1986–93. Built. It is a 3-floor housing development with a wedge-shaped, metal-clad 8-floor tower for the Internationale Bauausstellung. This, together with the Vitra Fire Station, was Zaha's first realised project. Hadid was one of three women commissioned to design social housing complexes, following the efforts of the Feministische Organisation von Planerinnen und Architektinnen to increase female contributions.

- Moonsoon in Sapporo. 1989–90. Built. Interior design of a restaurant with tables like "sharp fragments of ice" and a "plasma of biomorphic sofas".

- Folly 3 in Osaka, 1990. Built. Folly in the grounds of the Expo '90 fair, a "series of compressed and fused elements to expand in the landscape and refract pedestrian movement." Hadid describes the sculpture as a "half scale experiment for the Vitra Fire Station".

- Vitra fire station, in Weil am Rhein,1994. Built.

- Serpentine Gallery Pavilion in London, UK. 2000. Built.

- Serpentine Sackler Gallery in London, UK. 2013. Built.

- Hoenheim-North Terminus & Car Park in Hoenheim, France. 2001 Built.

- One-North Masterplan Singapore, 2001.

- Bergisel Ski Jump in Innsbruck, Austria. 2002 Built.

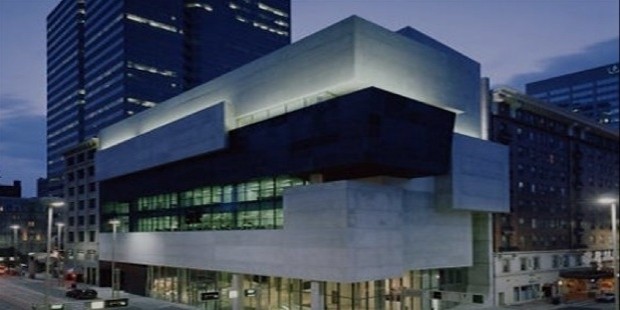

- Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, Ohio. 2003. Built.

- Ordrupgaard Museum extension in Copenhagen, Denmark 2001-05. Built.

- BMW Central Building in Leipzig, Germany. 2005. Built.

- Phaeno Science Center in Wolfsburg, Germany. 2005. Built.

- Maggie's Centres at the Victoria Hospital in Kirkcaldy, Scotland. 2006. Built.

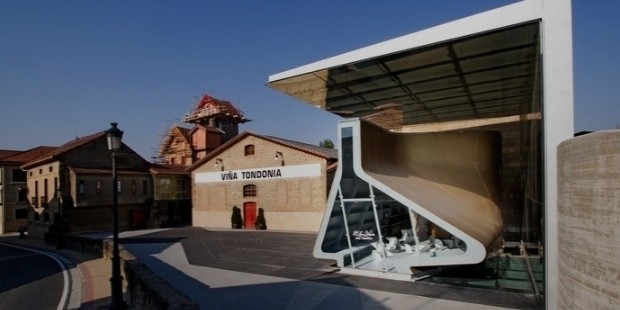

- Tondonia Winery Pavilion in Haro, Spain. 2001-06. Built.

- Eleftheria Square redesign in Nicosia, Cyprus. 2007. On hold.

- Hungerburgbahn stations in Innsbruck, Austria. 2007. Built.

- Bridge Pavilion in Zaragoza, Spain. 2008. Built.

- J. S. Bach Pavilion in Manchester, UK. 2009. Built. For the Manchester International Festival.

- CMA CGM Tower in Marseille, France. 2005-10. Built.

- MAXXI - National Museum of the 21st Century Arts in Rome, Italy. 1998-2010. Built. Winner of the 2010 Stirling Prize

- Guangzhou Opera House in Guangzhou, China. 2005-10. Built.

- Evelyn Grace Academy in Brixton, London, UK. 2006-10 Built. Winner of the 2011 Stirling Prize

- Sheikh Zayed Bridge in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. 2007-10. Built.

- London Aquatics Centre in London, UK. 2008-11. Built.

- Riverside Museum in Glasgow, Scotland, UK 2007-11. Built.

- Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center in Baku, Azerbaijan. 2007-12. Built.

- Pierres Vives Building in Montpelier, France. 2002-12. Built.

- Napoli Afragola railway station in Napoli, Italy. 2003-12. Ongoing.

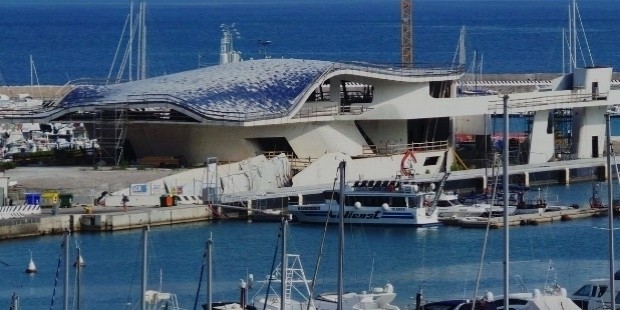

- Salerno Maritime Terminal in Salerno, Italy. 1999-12. Ongoing.

- Innovation Tower in Hong Kong SAR, China. 2009-13. Built.

- Dongdaemun Design Plaza & Park in Dongdaemun, Seoul, South Korea. 2007-14. Built.

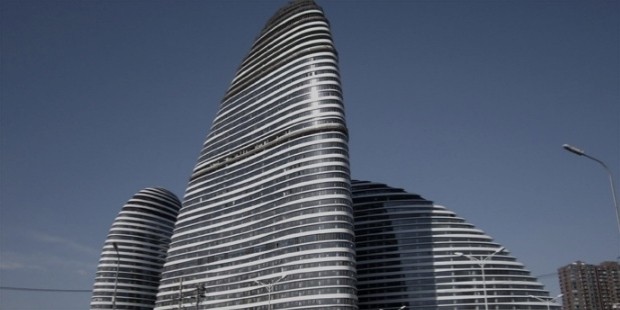

- Wangjing SOHO in Beijing, China. 2009-14. Built.

- Investcorp Building, St Antony's College in Oxford, England. 2013-15. Built.

- Mesner Mountain Museum Coroness in Kronplatz mountain, Italy. 2015. Built.

Proposed and Conceptualised Projects

- - Vilnius Guggenheim Hermitage Museum in Vilnius, Lithuania. 2008. Not realised.

- - Szervita Square Tower in Budapest, Hungary. 2006. Not realised.

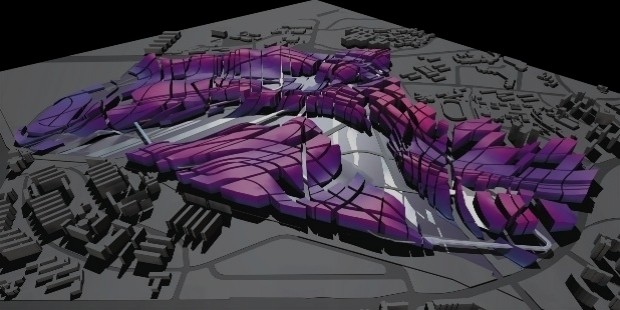

- - Kartal-Pendik Waterfront Regeneration Masterplan in Istanbul, Turkey. 2006. Not realised.

- - Cardiff Bay Opera House in Cardiff, Wales, UK. 1995 Not realised.

- - Grace on Coronation in Brisbane, Australia. 2014. Proposed. 3 residential skyscrapers with civic space within a new riverside park.

- - Azabu-Jyuban in Tokyo, Azabu Juban. 1986. Not realised. Commercial development on a "narrow site in a canyon of random buildings near the Roppongi district."

- - Tomigaya in Tokyo, Azabu Juban 1986. Not realised. Small mixed-use project related to the Azabu-Jyuban project, featuring an elevated angular glass pavilion as its centerpiece.

- - West Hollywood Civic Centre in Los Angeles, Azabu Juban. 1987. Not realised. Design for a civic centre in a "relatively context-free environment", allowing "objects [to] float and interact in a way that is only possible in wide-open spaces".

- - Al Wahda Sports Centre in Abu Dhabi. 1988. Not realised.

- - Berlin 2000 in Berlin. 1988. Not realised. Urban masterplan for a Berlin without the Berlin Wall, commissioned a year before the Wall's actual fall.

- - Victoria City Areal in Berlin. 1988. Not realised. Design for a re-development of a cruciform site on Kurfürstendamm, envisioning a "bent slab" of a hotel hovering above the street.

- - A New Barcelona in Barcelona. 1989. Not realised. This was a project of a "new urban geometry" for Barcelona.

- - Tokyo Forum in Tokyo. 1989. Not realised. Design for a municipal Cultural Centre, based on a "void - a glass container - out of which smaller voids are dramatically hollowed and which house the building's cultural and conference areas.

- - Hafenstrasse development in Hamburg, Hafenstraße. 1990. Not realised. Project of a mixed-use development in two gaps in a row of houses on the Elbe embankment, featuring angular, semi-transparent slabs on pillars.

Personal Life

Zaha was never been married. She wanted to situate all her focus on her career as an architect. Zaha’s net worth of $215million included stock investments, property holdings, a football team, a brand of Vodka, perfume and fashion line.

Awards

For her British Architecture, Zaha received her first award, Gold Medal Architectural Design in 1982. She won the Pritzker Price in 2004 and became the youngest and the first woman to achieve the award. Zaha’s design for Heydar Aliyev Center has won the Designs of the Year in 2014.

Death

On 31 March 2016, Hadid suddenly died of a heart attack in a Miami hospital, where she was being treated for bronchitis.

Awards

- 2013

Veuve Clicquot UK Business Woman Award

- 2012

Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) Honours for services to architecture

- 2012

Jane Drew Prize

- 2010

RIBA European Award for MAXXI

- 2006

RIBA European Award for Phaeno Science Centre

- 2005

RIBA European Award for BMW Central Building

- 2005

Designer of the Year Award for Design Miami

- 2005

German Architecture Prize for the central building of the BMW plant in Leipzig

- 2004

Pritzker Architecture Prize

- 2002

Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE)

No comments:

Post a Comment